Rejecting Development: Narrowing the Parameters of the Responsibility to Protect

Professor Adrian Gallagher summarises the key findings of his latest research article in which he concludes that the RtoP should not engage with long-term development issues.

The Responsibility to Protect (RtoP) has a controversial relationship with development which has led to divisions between academics and governments, however, this is not often discussed in the literature. To address this, I conducted an extensive study and published a new article titled An International Responsibility to Develop in order to Protect? A Responsibility too Far. I summarise its key findings here.

The article divides academic positions into three camps: minimalist, middle ground, and radical.

- Minimalists offer a narrow view of the RtoP, seek to distance the norm from long-term structural prevention and argue that it should not engage with long-term development.

- Middle ground academics claim that the RtoP should engage with development but refrain from broader debates which call for international socioeconomic reforms to be included in ‘mass atrocity' prevention strategies.

- Radicals either challenge or reject the RtoP for two reasons. First, they argue that the RtoP legitimises underlying structures and on-going practices which enable mass atrocities to occur in the first place. Second, because they view underdevelopment as a significant root cause of mass atrocities they put forward a normative argument that global socioeconomic structures need to be changed in order to prevent atrocity crimes.

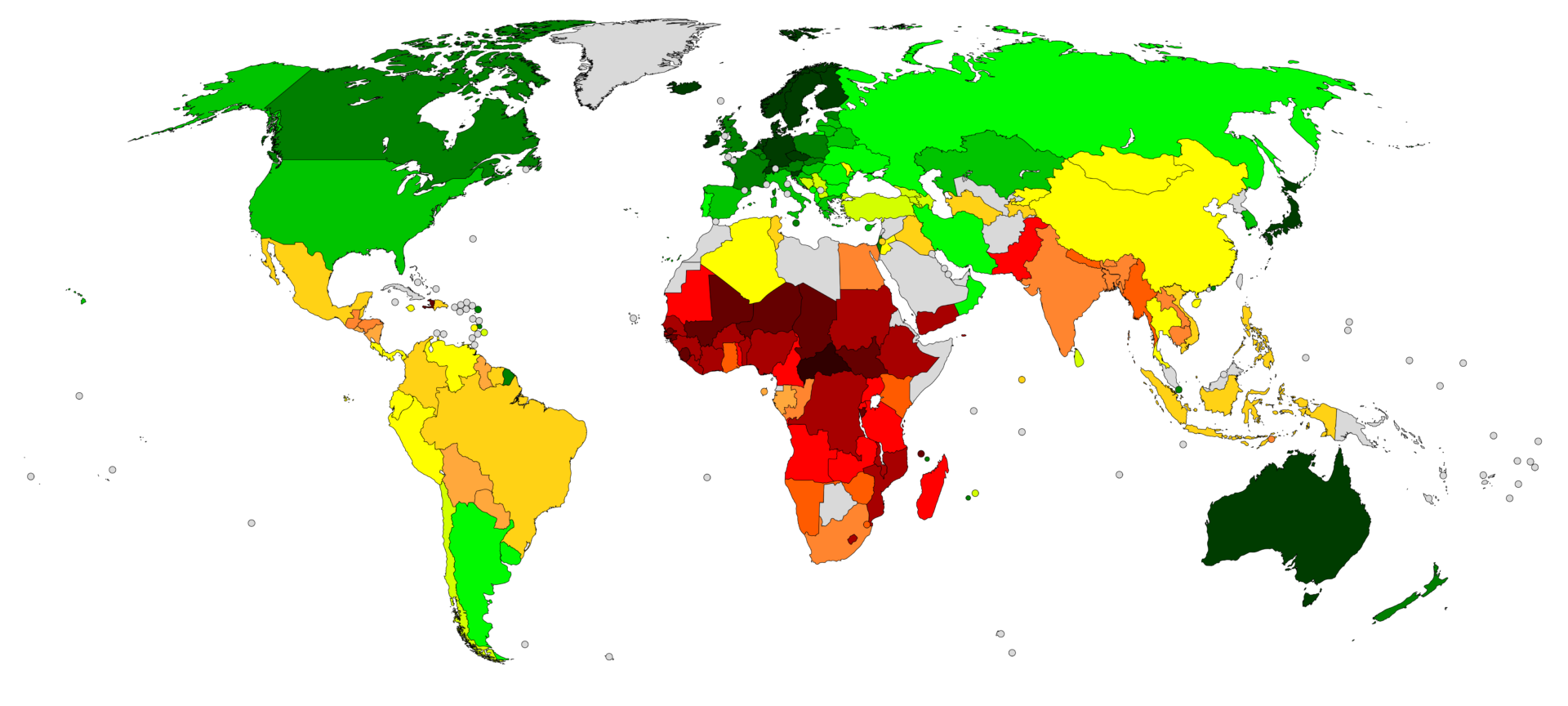

To help shed new light on the debate, the article analyses thirty-seven countries and Human Development Index (HDI) data (1990-2020) to establish patterns in HDI data for countries that have experienced mass atrocities or for which there were serious concerns of them occurring, both with regard to status/absolute positions in the ranking, and with regard to change/trajectory. It puts forward eight key findings:

- Mass atrocities or serious concern of such atrocities occur in each type of HDI country: Low, Medium, High, and Very High (albeit just once in the latter).

- The vast majority of atrocities or the raising of serious concerns of atrocities occur in Low and Medium ranked countries.

- Medium ranked countries are just as likely to experience atrocities as Low ranked countries.

- The lowest ranking countries (bottom twenty) are disproportionately vulnerable to atrocity crimes.

- Many Low ranking countries have not experienced mass atrocities this century.

- The majority of countries experience positive HDI growth in the lead up to, and after, their atrocities or serious concerns being raised of atrocities.

- Only one country experienced a decline in HDI status in the year following their crisis.

- A smaller, yet significant, number of cases evidence HDI regression in the lead up to their atrocities or serious concerns being raised of atrocities.

The findings underline just how complex the relationship between mass atrocities and socioeconomics is, but this in itself is important because it reflects minimalist concerns and in turn, the article defends the minimalist position that the RtoP should not engage with long-term development issues.

That said, it often feels as though there is an unspoken tension lying at the heart of the Responsibility to Protect discourse. On one hand, there is a widespread consensus that a ‘case-by-case’ approach is needed, but on the other hand, there are on-going attempts to create principles, rules, and recommendations that aim to improve mass atrocity prevention strategies overall. Regarding the former, micro studies (case study and comparative case study analysis) provide an in-depth understanding of mass atrocity and/or mass atrocities. Regarding the latter, macro level analysis seeks to go beyond case study analysis in order to provide generalisable recommendations or even an overarching theory. The point here is that although this study sets out a normative recommendation – the RtoP should not engage in development – it comes with a caveat as case-by-case requirements will, at times, expose that macro level rules and principles should not be followed.

Whether you agree with the argument made, or not, the study raises points that are important for future research, and in closing, I raise two of them. First, which countries have experienced mass atrocities in the 21st century? Through an amalgamation of different data sets, the article identifies thirty-seven countries that have experienced mass atrocities or for which there were serious concerns of them occurring. Undoubtedly, the sensitive nature of the subject nature will lead others to argue that case X should or should not be included and I welcome such future discussion.

Second, development means very different things to different actors. As the 2019 formal UN General Assembly debate on the RtoP evidences, seventy-three states and the European Union spoke in favour of ‘sustainable development’ aiding mass atrocity prevention. This might suggest a consensus, but there is significant division over what this actually entails. Whilst one can argue such contestation is to be expected and is positive, the fundamental differences involved should not be overlooked, those that argue the RtoP should engage in development need to address this and we should not proceed on the premise that there is an overarching consensus on this issue.

Adrian Gallagher is a Professor in Global Security and Mass Atrocity Prevention in School of Politics and International Relations at the University of Leeds. He is also co-director of the European Centre for the Responsibility to Protect and Editor of the journal Global Responsibility to Protect.

Image credit: Countries by inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (2019) by JackintheBox is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

If you are interested in submitting a blog post for the ECR2P’s Fresh Perspectives series, then please contact Dr Richard Illingworth by Email (r.illingworth@leeds.ac.uk) or Twitter (@RJI95).